As a white mother to three mixed heritage children, I spend a lot of time thinking about identity and how my own children experience the world so differently to me. This is the reasons I was so determined to get access to President Obama’s campaign in 2008 , to spend time with the world’s religious leaders.

In 2015 it compelled me to create a series of work about Rio Carnival, The Dance of Colour.

I was drawn to Brazil because of its complex culture and unique history. In 1888 Brazil was one of the last Western countries to abolish slavery. Over ten times the number of enslaved Africans were forcibly transported to Brazil compared to North America, meaning that today Brazil is home to more people of African heritage than any country outside Africa. Unlike other colonies, many Portuguese settlers were single men and inter-marriages were common. Brazil was not subjected to state sponsored segregation or apartheid, so in the popular imagination the country is widely considered to be a harmonious racial democracy, with a unique fluidity between European, African and indigenous heritage. Today 47% of Brazilians identify as mixed-race. In truth the situation is far more nuanced, and racial discrimination and inequality is pervasive.

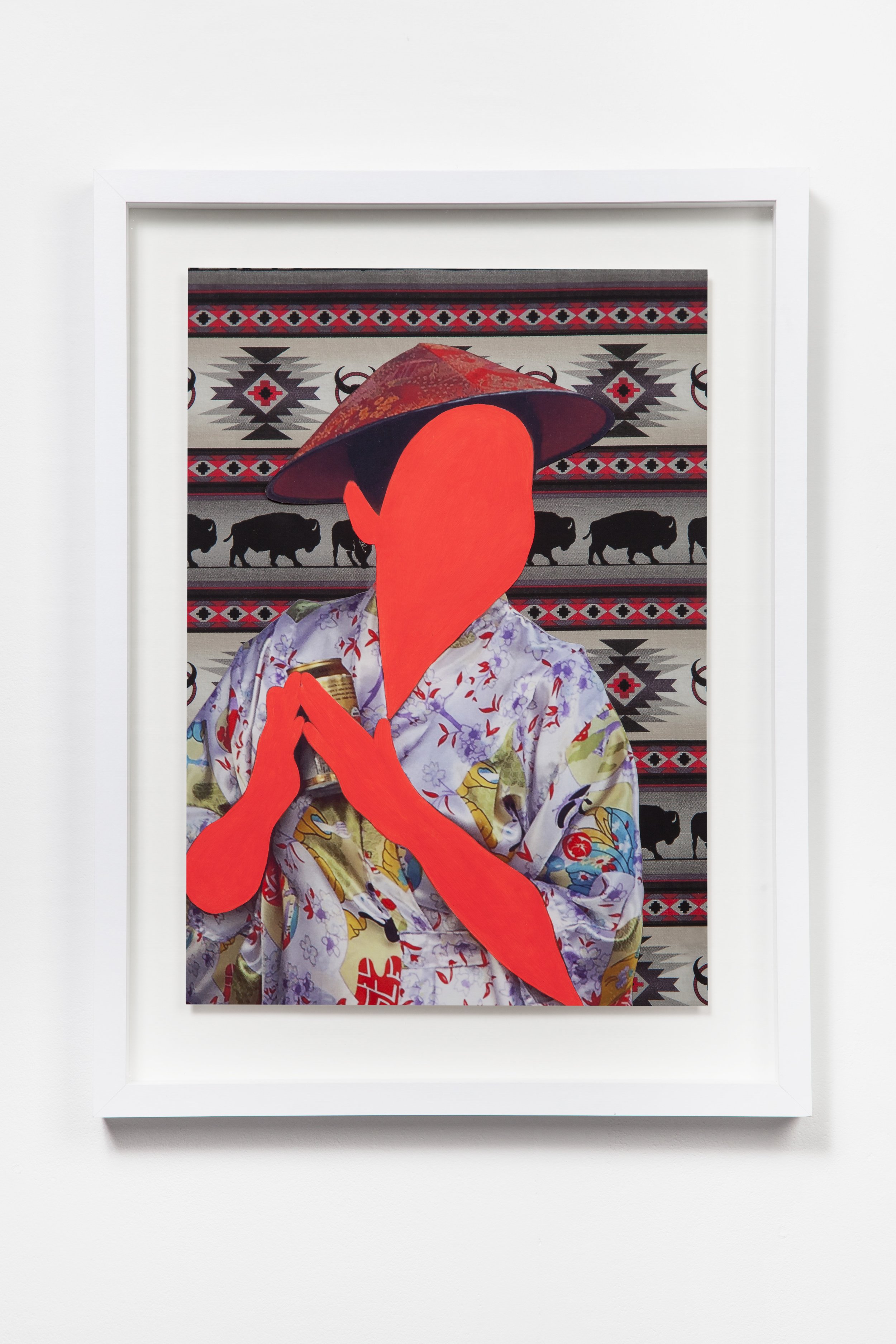

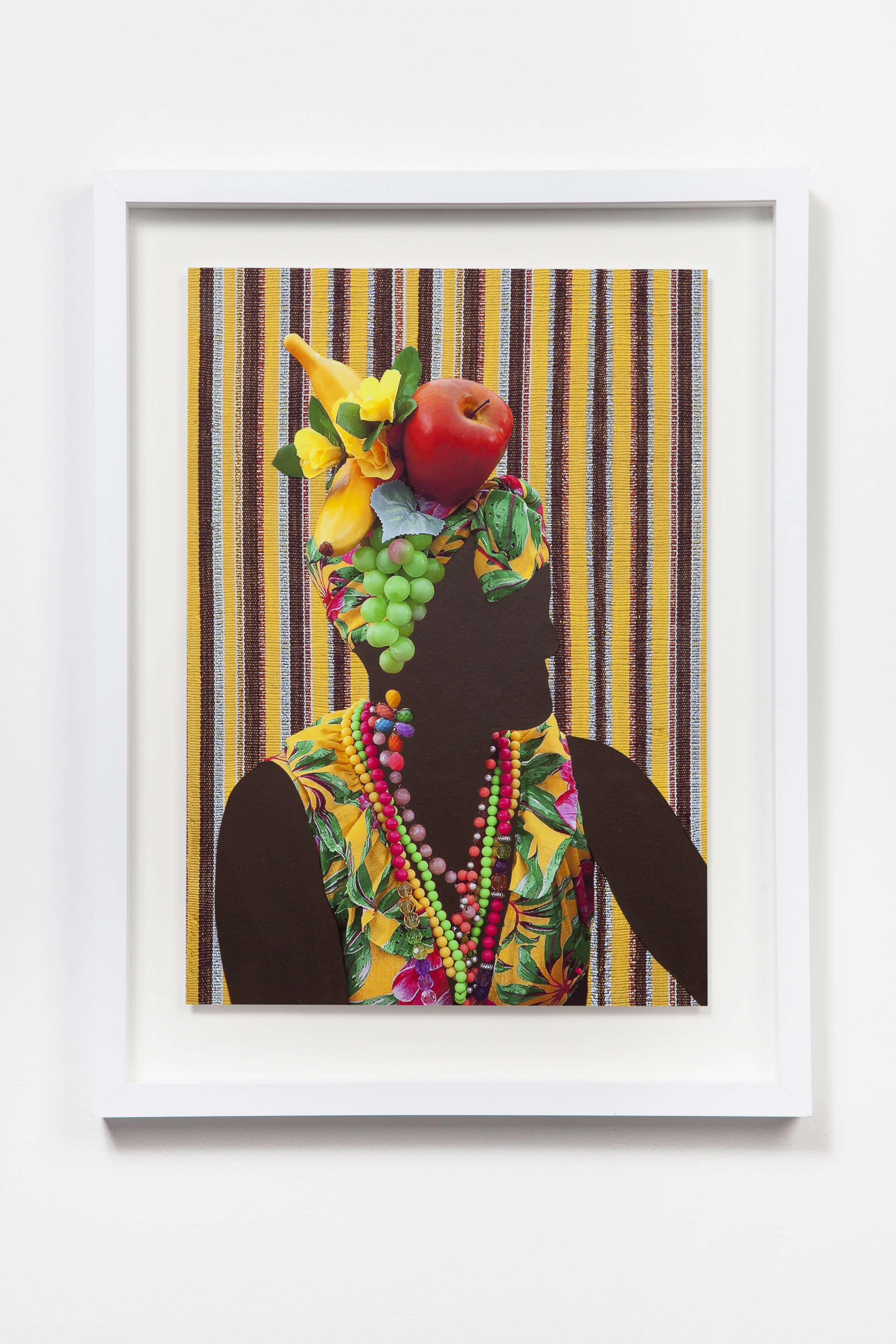

I wanted to visit Brazil to understand and explore how Rio Carnival embodies and carries this history. I really immersed myself in the culture and was even lucky enough to dance in the parade at the Sambadromo! Carnival began as a pagan festival in Ancient Egypt, and was assimilated by the Greeks and Romans. Over time, carnival evolved and was overlaid with Christian meaning, it came to be associated with the period of lavish Italian costume parties and decadent feasting before Lent. Colonialism and the spread of Christianity meant that carnival was exported around the world. In Brazil this European tradition became fused indigenous and African rituals, music, dancing and costume. Today Rio Carnival is regarded as a celebration of the country’s mixed heritage, and as a moment of freedom of expression.

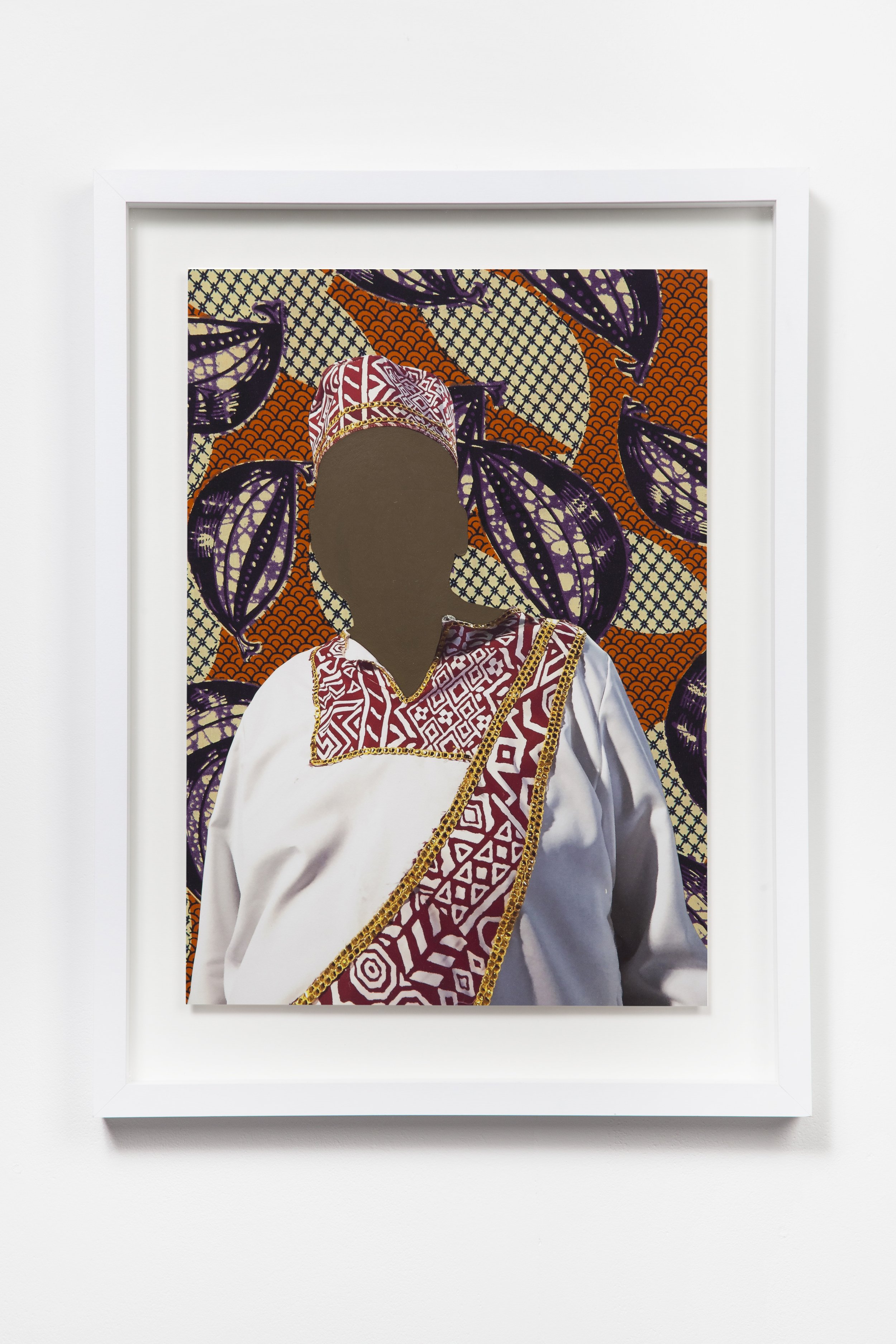

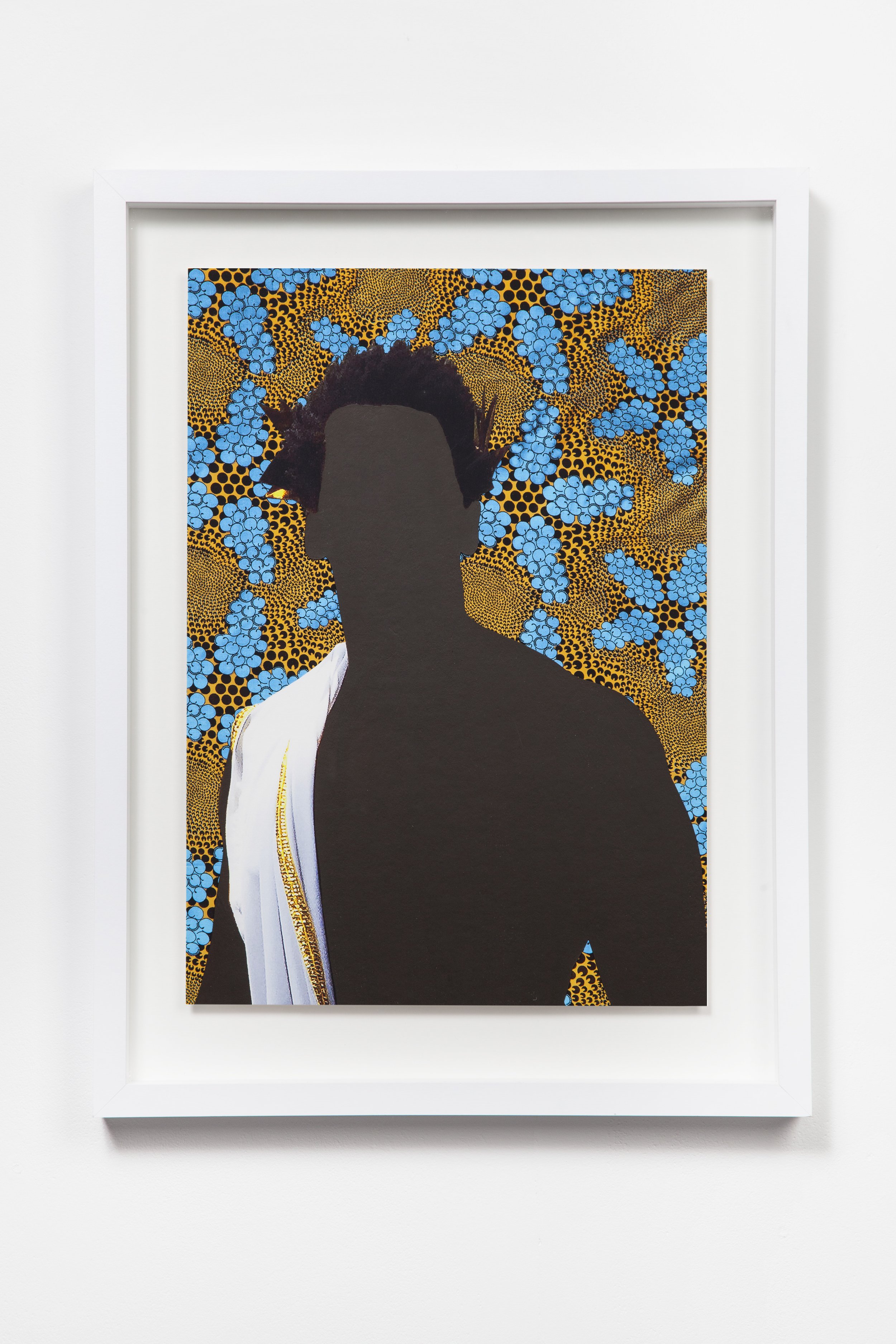

Carnival is a day when usual social orders are suspended. It provides an opportunity for people to temporarily shed their identity and adopt a different persona that can blur boundaries and transcend hierarchies. Carnival is a space in which people have a chance to explore race, gender and sexuality in all kinds of ways.

Having explored racial dimension of carivinal in more depth in the past, I wanted to consider the complexities of how gender and sexuality are expressed, performed and displaced during carnival.

Brazil was hit particularly hard by the pandemic, and after two years of cancelation, this years carnival was highly anticipated.

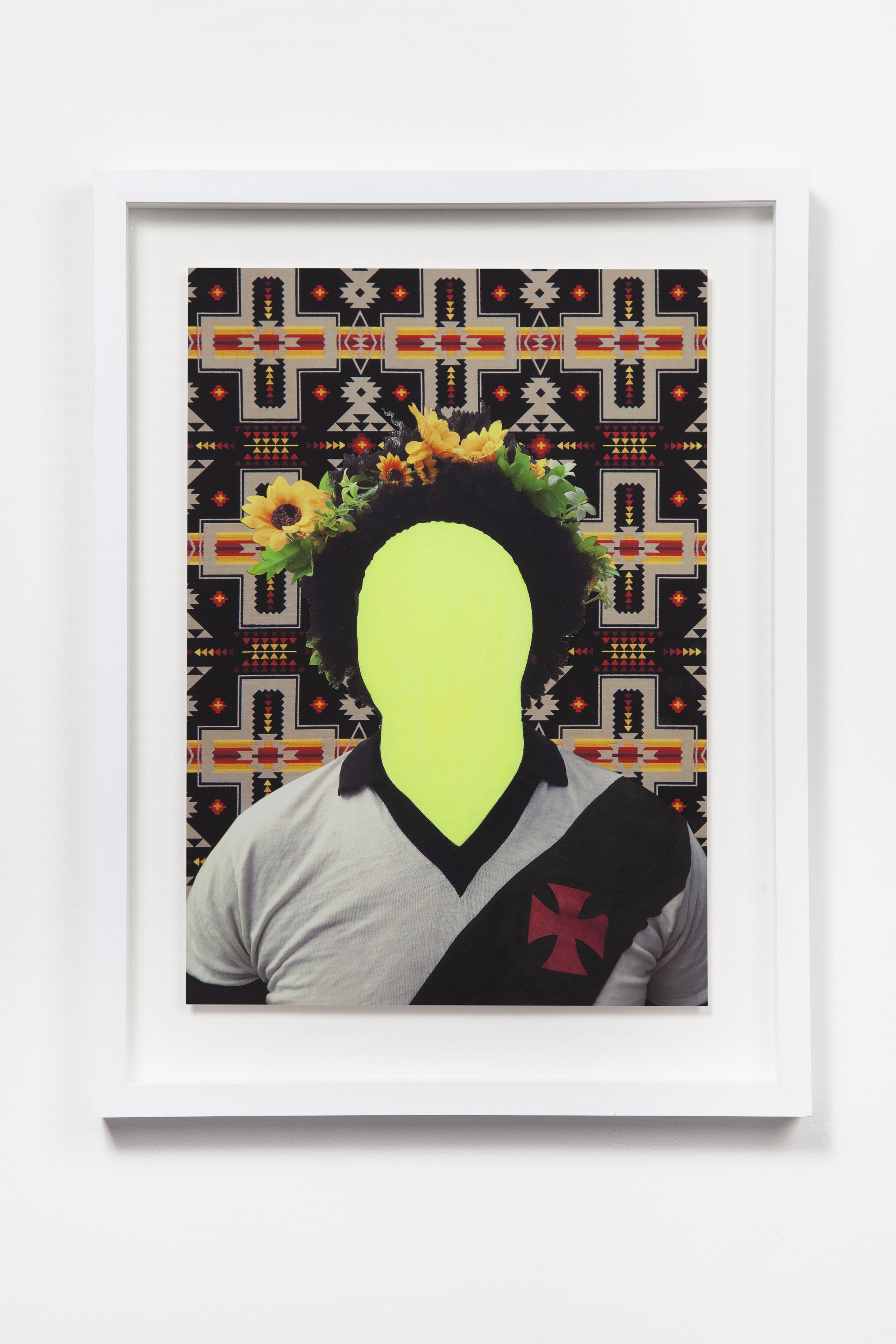

For some people it is a moment to forget about society's rules and expectations, the flamboyant costumes, joyous dancing and ecstatic atmosphere allows them to subvert traditional roles and explore their identity more fluidly. There are blocos celebrating afro-Brazilian and indigenous culture, celebrations of Candomblé Orishas, samba schools led by drag queens and Afro-feminist parade floats. Carnival is an opportunity for people to perform or masquerade their identity as they choose.

For others, carnival embodies the sexual and racial politics experienced every day in Brazil. A country with continuously high levels of gender based violence, against women, particularly transgender women and those of Afro-descent.

Since I made this work in 2015, events in Brazil have meant that it’s even more vital to focus on carnival as a site of resistance.

For example, the “Barbie Fascists” have used carnival to protest against the current government, and other feminist movements have campaigned against sexual harassment and the hyper sexualised costumes and objectifying imagery of the "carnival queens”.

Samba schools have been reclaimed and used a a way to teach black history and culture. The Mangueira samba school has used the carnival to pay tribute to unsung black and indigenous heroes, such as Marielle Franco, and in 2020 told the story of Jesus born in the favela to protest the government’s divisive rhetoric. This year the Grande Rio Samba School were crowned champions of the parade, with costume and floats that highlighted prejudices against Afro-Brazilian religions and paid tribute to Exú, a god revered by many African cultures. Each float in the parade tells a different story, or highlights a different political issue.

Despite the complexities and contradictions, carnival remains a symbol of hope. On one level it has always been a day to forget about your troubles and have fun, a day to protest and rage, or a day for unrestrained freedom of expression and up-ending social, sexual, racial and political identities. Carnival is political, it takes a great deal of strength to express your true identity, and there is a power that comes from simply being visible, from taking up space. Carnival is an enduring and powerful site of both resistance and joy.

For more information on Carnival Beat and Bate Bola click here.