House Slave - Field Slave I (2007) Oil and 24k gold leaf on canvas H150 x W200 cm Permanent collection of International Slavery Museum, Liverpool.

Today is Anti-Slavery Day, an important and crucial campaign to raise awareness and inspire action to end modern slavery.

To many of us, slavery is something firmly relegated to the past, but despite the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade in 1807, there are still approximately 49.6 million victims of slavery and human trafficking around the world today. That is one in every 200 people - with women and girls making up 71% of all victims.

In 2007, to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the abolition of the slave trade, I created a portrait in collaboration with Anti-Slavery International called House Slave – Field Slave. The imagery was inspired by artefacts and extraordinary photos provided by Anti-Slavery International. I created a large scale altarpiece-style triptych, using oil paint on canvas, to create iconic imagery of the feet of known slaves. We wanted to reflect on how enslavement strips a person of their identity; I decided not to include the rest of their figure or faces, to reflect this loss of bodily autonomy. I used objects, symbols, and other semiotic markers to capture the diverse experiences of contemporary slavery including bonded labour, child exploitation, human trafficking and forced marriages.

I used the imagery and connotations of the “altarpiece” lavished in 24k gold leaf in order to evoke the idea of veneration, exultation, divinity and most importantly value. I used the rarest and most expensive gold available to attribute this value to people that are treated as worthless or disposable. I use 24k gold to raise questions about value, identity, and race in so much of my work. I have used it in Day 2, Struggle from In Seven Days… to reflect on the complexity, value and identity of Obama’s mixed heritage, and to honour my own children. Most recently, I have used gold leaf in my Sunburst series to interrogate how gold has been used to depict celestial heavenly light and the ways in which this has been utilised throughout history to reinforce the value of whiteness.

House Slave – Field Slave was exhibited at Dulwich Picture Gallery in 2007, alongside preparatory studies, which inspired the work. I ran educational workshops with young people, based on teaching the principles of visual storytelling. It was exhibited as part of Black History Month at Bruce Castle Museum in 2010. House Slave - Field Slave is in the permanent collection of the International Slavery Museum, Liverpool.

I wanted, in this blog post, to consider two other artworks which were important to me whilst making House Slave - Field Slave: Head of a Man by John Simpson (1827) and Lawdy Mama by Barkley L. Hendricks (1969). These two artworks both use oil paint and gold leaf to evoke religious imagery and questions of value, as well as raising issues surrounding race, identity and slavery.

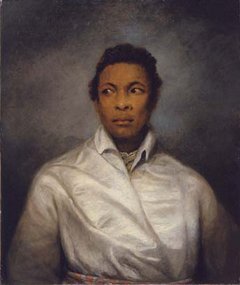

Head of a Man by John Simpson (1827)

Head of a Man (originally titled Head of a Black and later Head of a Negro) is a life-size study of a model’s head, the oval shape and gold tones resemble religious works or maybe even a halo that illuminates the figure. The subject has a melancholic manner and looks off into the distance, his expression especially reminiscent of many paintings of Christian Saints. According to the Tate, this may have been an attempt to appeal to the morality and empathy of white viewers and to draw attention to the brutality of the slave trade and humanise Black people in a systemically racist society. However, this piece has also been interpreted as a depiction of heroic and admirable Blackness, that the man’s heavy red cloak has an air of prestige, and that his stance and facial expression make him look valiant and brave.

Although exhibited originally as an anonymous figure, the model appears to be the American actor Ira Frederick Aldridge (1807–1867). Aldridge enjoyed huge success in Europe and was the first African American actor to play Othello. He was the subject of several paintings in the early stages of his career. However, in Head of a Man, Aldridge is depersonalised. It is not a portrait, but a character study so it is important to revisit his identity when we view this work today.

Head of a Man is exhibited at Tate Britain where it stands out for being one of the few works depicting a Black individual created in its time by a British artist. It is linked to another of Simpson’s large subject paintings, The Captive Slave, which shows the same sitter but in half-length format, manacled to a bench. Although the slave trade had been made illegal within the British Empire in 1807, slavery continued in British colonies until the 1830s and remained a hugely divisive political issue. Simpson’s paintings have been interpreted as important interventions in the dispute about race and slavery in their time. They were interpreted as an important abolitionist statement and demonstrate the power of the visual image.

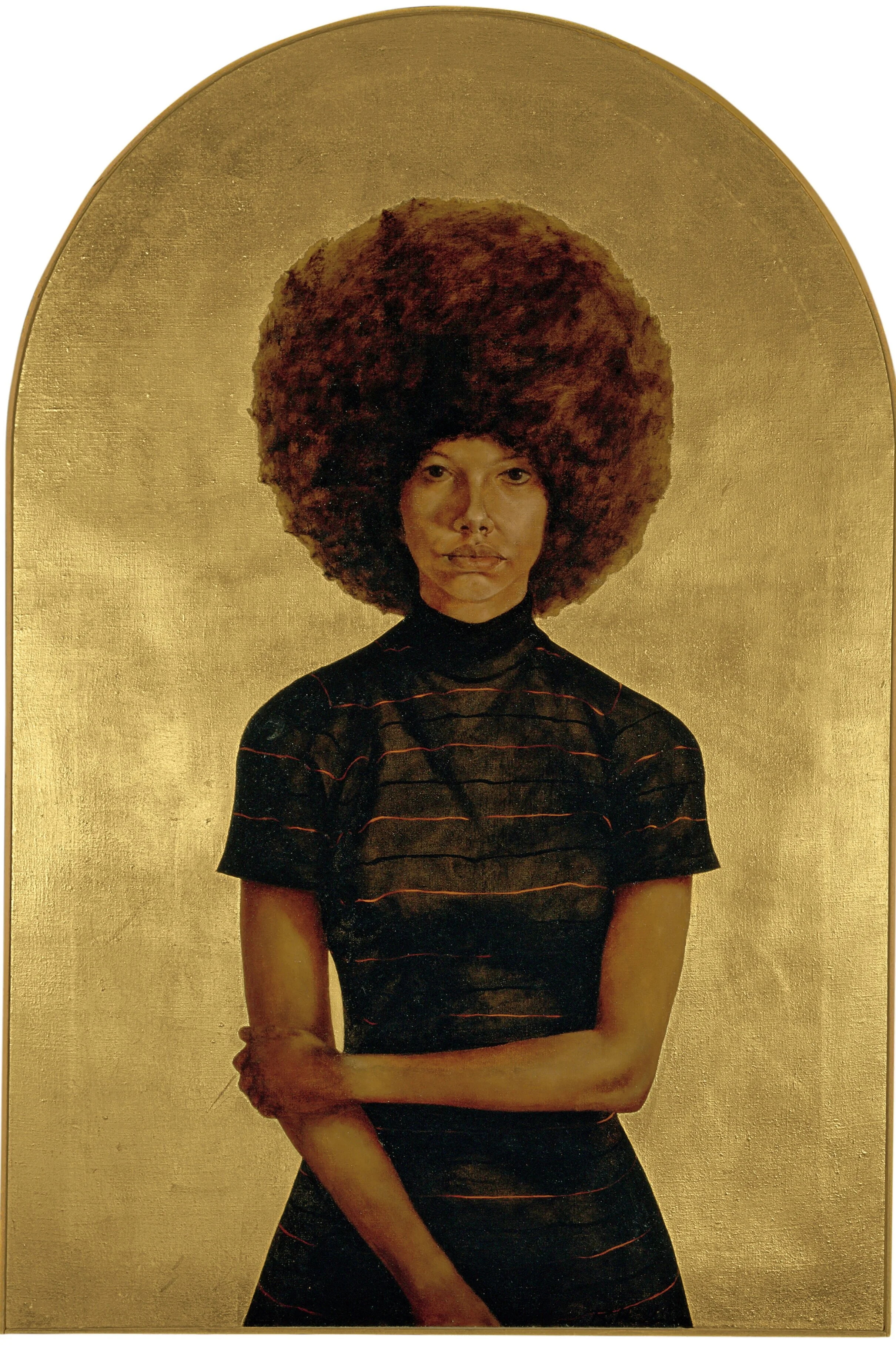

The flattened figure, arched canvas and gold leaf used by Barkley L. Hendricks in Lawdy Mama especially references Byzantine and medieval religious icons, evoking the celestial realm. The Studio Museum in Harlem states: “Elevating the Black figure to a subject worthy of veneration, the artist draws a visual comparison between his sitter and iconic depictions of Kathleen Cleaver, Angela Davis, and other women of the Black Power movement in the 1960s. The painting also comments on the overall lack of painted representations of Black bodies.”

The woman in the painting is the artist Hendrick’s cousin, Kathy Williams. She gazes directly out to the viewer, her expression is soft but strong. In contrast to Head of a Man, her posture is more relaxed, she is dressed in more casual clothing and importantly and powerfully wears a natural hairstyle, framed beautifully by the arch of the canvas. Her hair itself visually creates its own reference to a celestial halo. Henrick’s has created a modern-day icon that celebrates and monumentalises all black women.

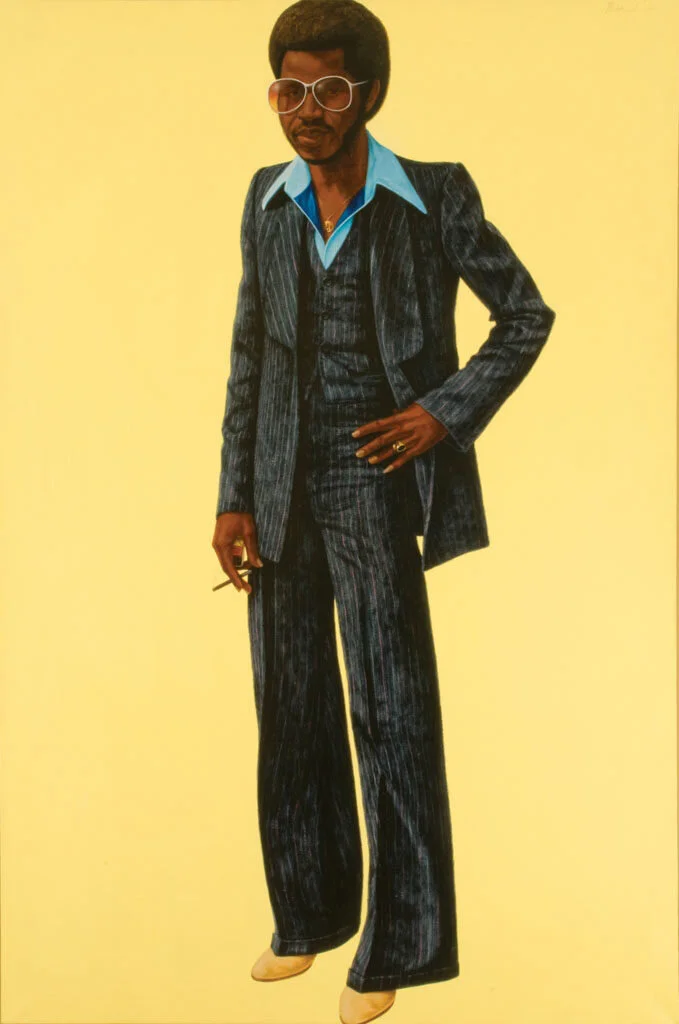

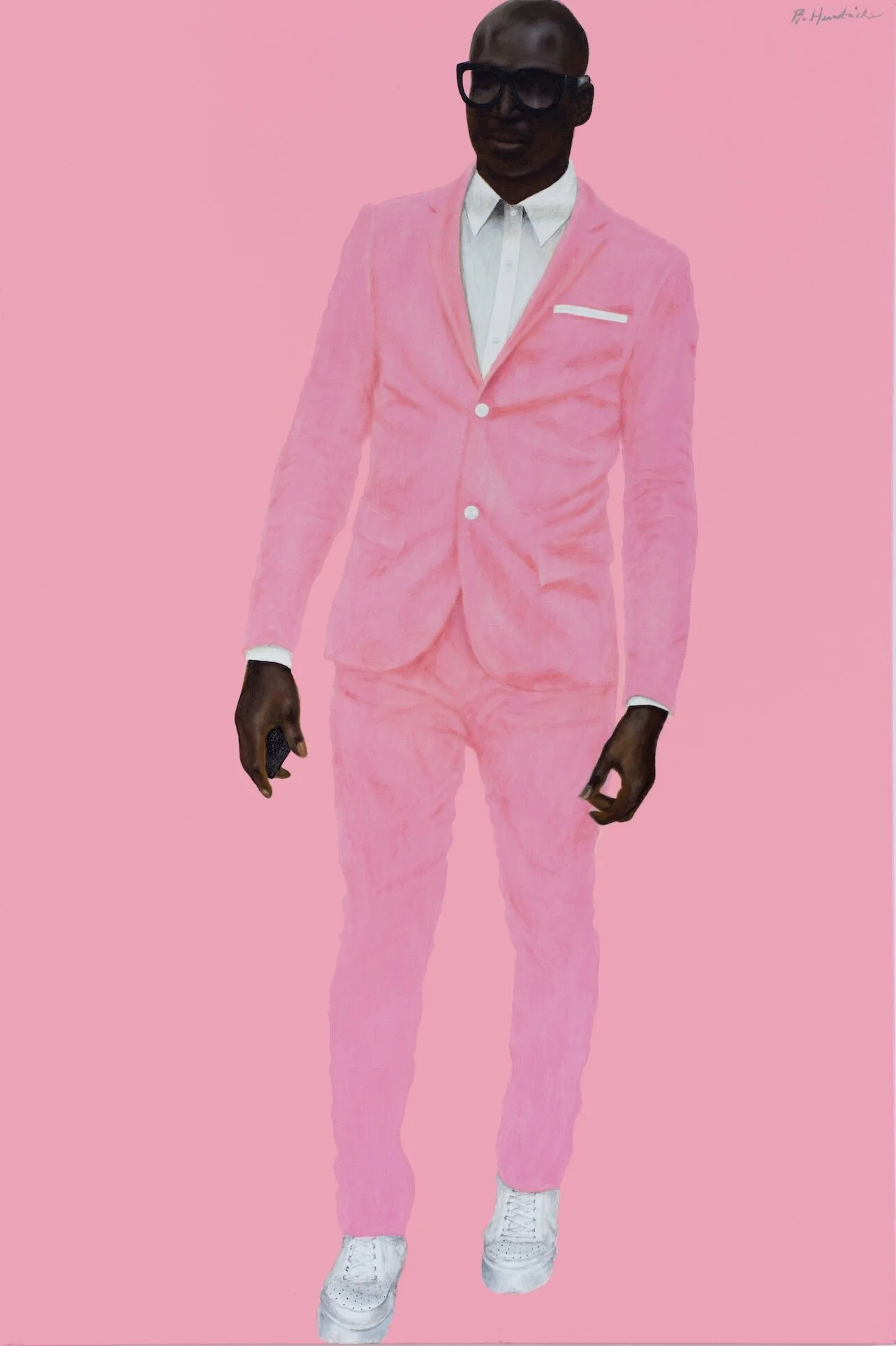

Lawdy Mama, and Hendricks’ oeuvre of portraits of African Americans, have an attitude and style that reflect the challenges and upheavals of the societies in which they were created, as well as the rise of black power and pride. Although Hendricks claimed he was not an activist, that his icons of black power were a-political, this work is a radical and powerful response to the lack of depictions of black people in the canon of Western Art. Henry Louis Gates writes “His self-possessed, stylish and assertive subjects obliterated any traces of subjugation or tinges of stereotype…Hendricks’s unapologetic and complex depictions of black personas both challenge the cultural status quo and gracefully take their space in the history of Western Art”.

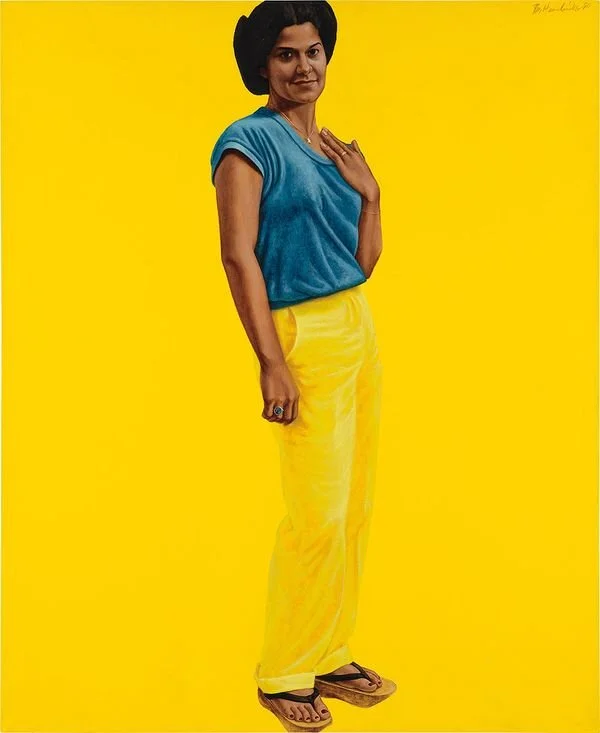

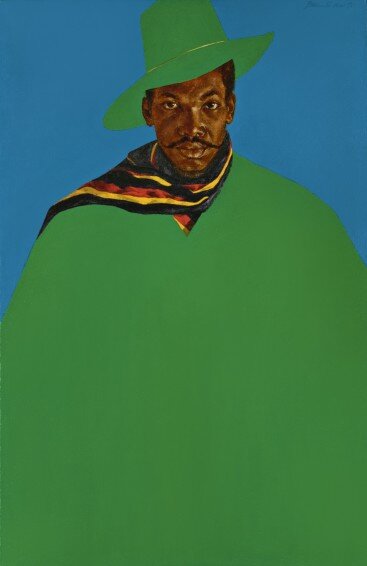

A selection of other works by Barkley L. Hendricks:

Much of the information on The Head of a Man came from this excellent article - The Racial and Identity Politics of Head of a Man

For more information please visit:

https://www.antislavery.org/slavery-today/modern-slavery/

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2019/feb/25/modern-slavery-trafficking-persons-one-in-200

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/193664/the-captive-slave-ira-aldridge

https://www.jstor.org/stable/41614836

https://shadesofnoir.org.uk/head-of-a-man-visual-analysis/

https://studiomuseum.org/node/60849

https://latimesblogs.latimes.com/culturemonster/2009/05/barkley-l-hendricks-at-the-santa-monica-museum-of-art.html

https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2017/04/remembering-barkley-l-hendricks-a-master-of-black-postmodern-portraiture/523518/

https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/in-focus/family-jules/iconic-portraits