I wanted to write about my latest series of works: Sunburst and all the research, thought and reflection that went into making them.

These artworks started in my attic studio soon after having my first two children, while I was busy travelling to and from America creating In Seven Days...

Making In Seven Days… took years, it was a truly gargantuan task!

We easily forget that Obama’s election was unexpected and how at that moment people around the world really felt like the impossible had been achieved; a black man becoming the most visible, powerful man on the planet. It was the culmination of so much history. I felt tremendous pressure when making this work because this wasn’t my story, it was a global story with so many people invested in it.

I knew I needed to distil the themes, messages, people, and heritage contained in this story, and to chronicle it for future generations in a way that would not just reflect that exact moment, but would continue to have meaning for many years to come. It felt like a massive responsibility and there were times when I really struggled…

In my studio, I had some gold and plaster cherub ornaments that I had inherited from my granny - fantastically decorative Victoriana angels which she called putti. The idea of angels, of seeking the divine, inspired me to keep going and to look for spiritual guidance. These little plaster-cast angels got me thinking, not just about my own guardian angels, but also about all the people that had an interest in this story, who could guide me in making it, from Frederick Douglas to my mother-in-law, and from Mandela to our black and white African ancestors, as well as my own children. I reflected on my motivations to make this work, as a white mother of mixed-heritage children. I wanted to capture this story for them, and I thought deeply about how they would experience the world differently from me, purely by virtue of their skin colour.

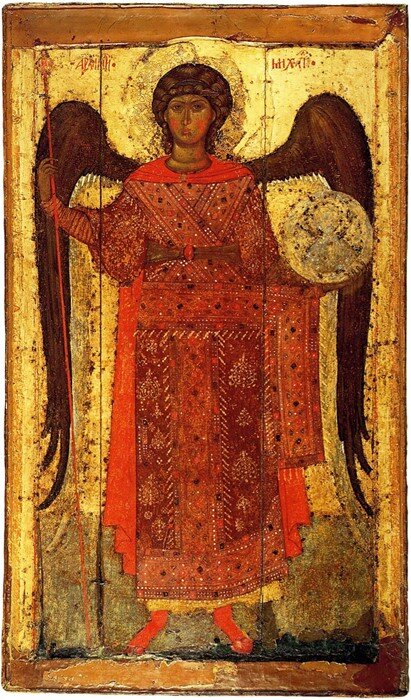

As I looked at my cherubs, I started thinking about their role as an enduring symbol throughout the canon of Western art. They’ve been used in a multitude of ways from Ancient Greece, to early religious imagery in the Abrahamic faiths, to the Renaissance, all the way up to the ornate decorative cherubs in my studio. But, if angels are meant to be the embodiment of innocence, love, and hope, or the representation of souls in heaven, why are they almost always male, and exclusively depicted as white?

There is an absence of people of colour in the entirety of Western art history. Important research is being done to re-discover and understand some of the hidden figures from Olympia’s maid to the Magi, to Saint Maurice. But, on a personal level, I’ve always been interested in the way in which the Holy Family has been whitewashed. It began in the Byzantine era when Jesus was depicted in the image of the Emperors, such as the Christus Ravenna Mosaic, with shimmering gold tesserae tiles conveying both royalty and divinity. But it was really during the Renaissance that the Virgin and child, a Middle Eastern family, were depicted with white skin and European features. They were, again, lavished in gold. Gold is a reflection of celestial heavenly light, but it also served to elevate the value of their whiteness, to confirm its worth, and legitimise its position at the top of the hierarchy.

The whiteness of the holy family, as well as of angels and cherubs, was highlighted to such an extent that whiteness became synonymous with divinity. Over the centuries the association of heaven with whiteness became intertwined with white supremacy, colonialism, and nationalism. To me, this really reveals the importance and pervasiveness of the stories we tell about ourselves, and the ways the visual image plays such a vital role in how we understand the world around us, we infer so much about how our society values people from these depictions.

Byzantine Mosaic of Christ and the angels, Basilica di Sant'Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna, Italy, 6th century.

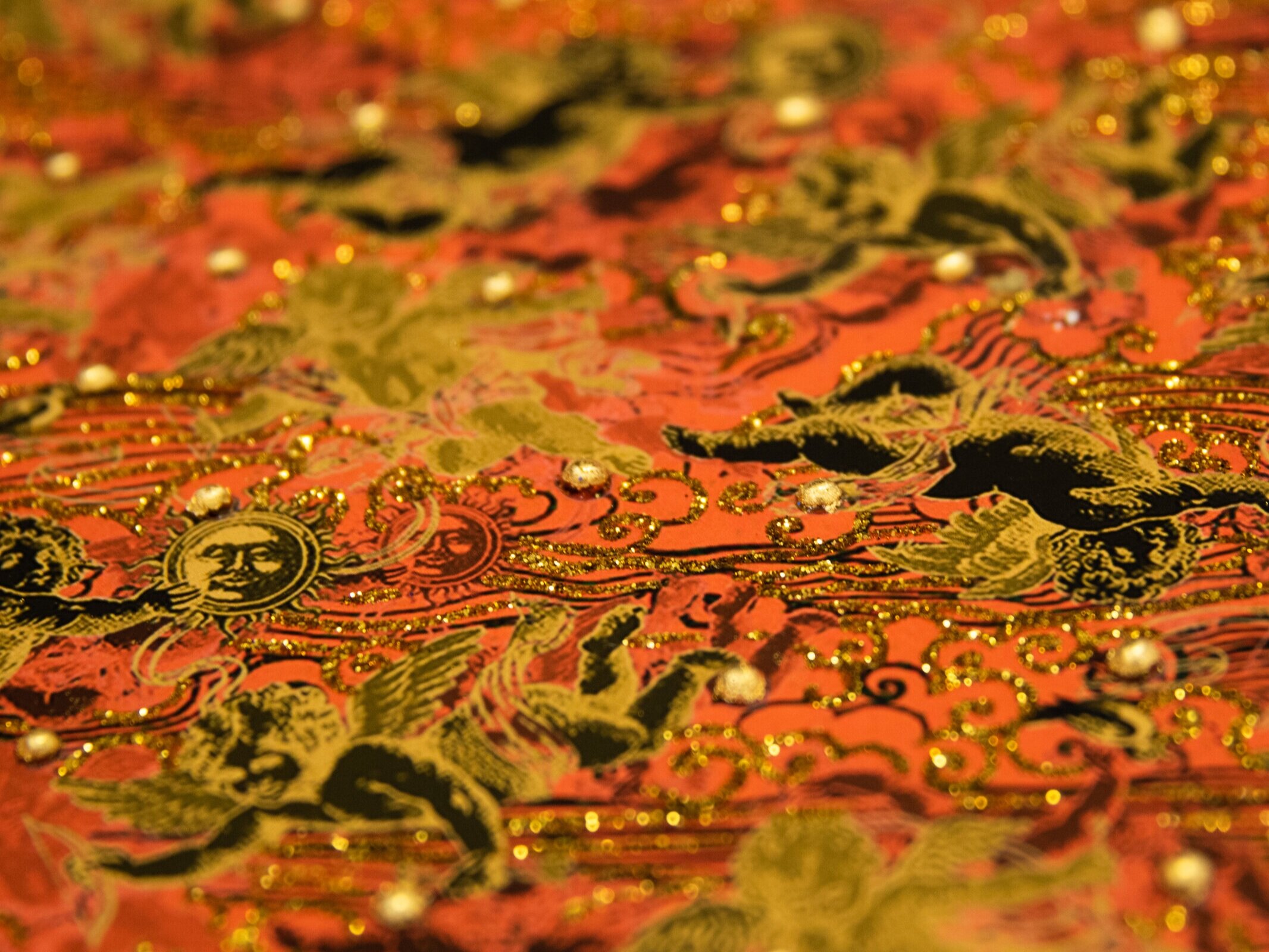

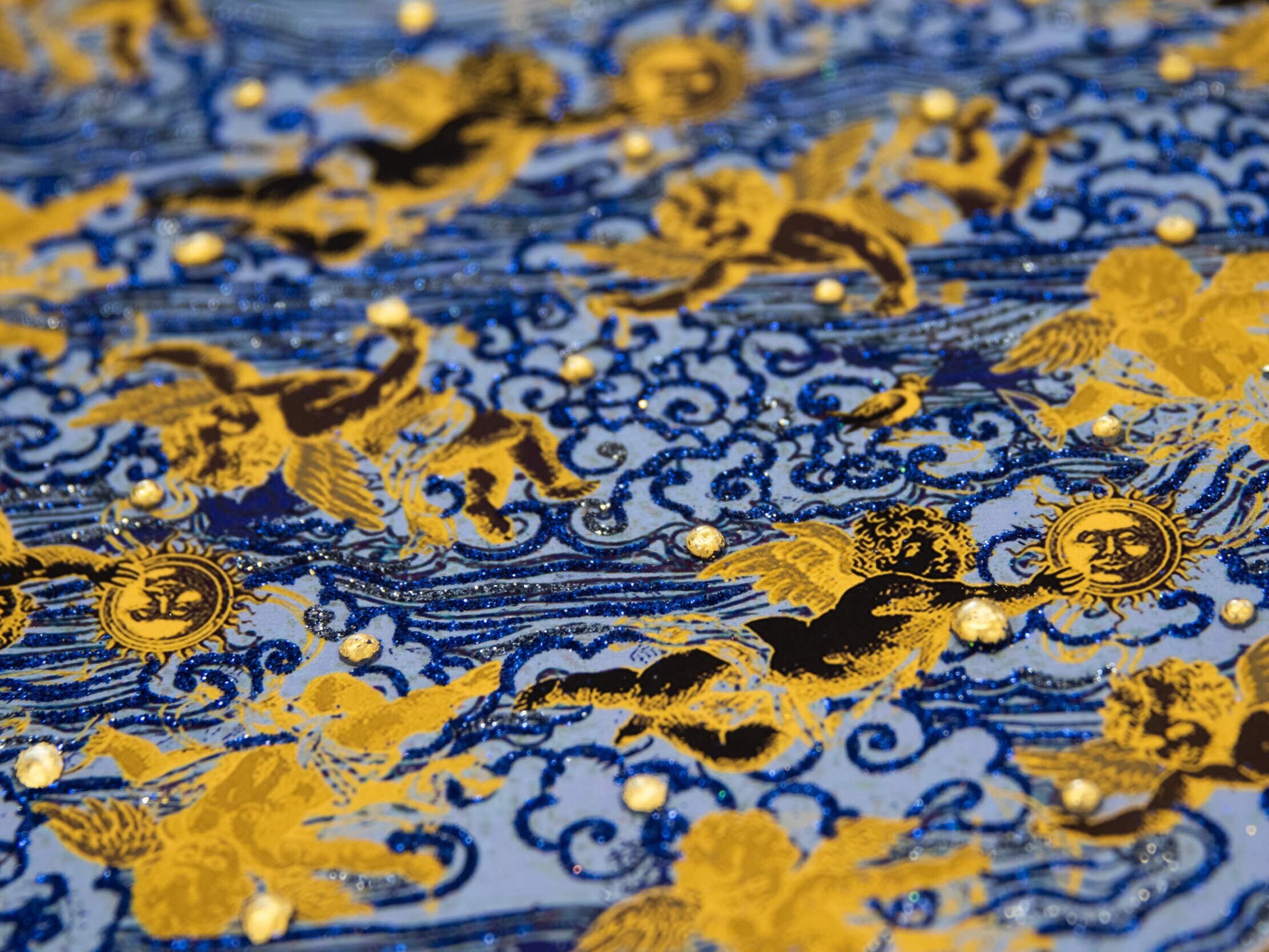

I wanted to harness the transformative power of art in shaping our understanding of the world and ourselves, so I started painting cherubs with different skin tones. I referenced the long history of paintings of angels, but particularly focused on the exuberant grandeur of the Baroque and Rococo periods. I took the ornate and flamboyant cherubs of this period and really embraced their extravagant sensibility, but I reimagined them to look like all children of the world, including my mixed heritage children and black nieces and nephews. I reclaimed their magic, and the final result is a joyous image which reflects what heaven looks like to me.

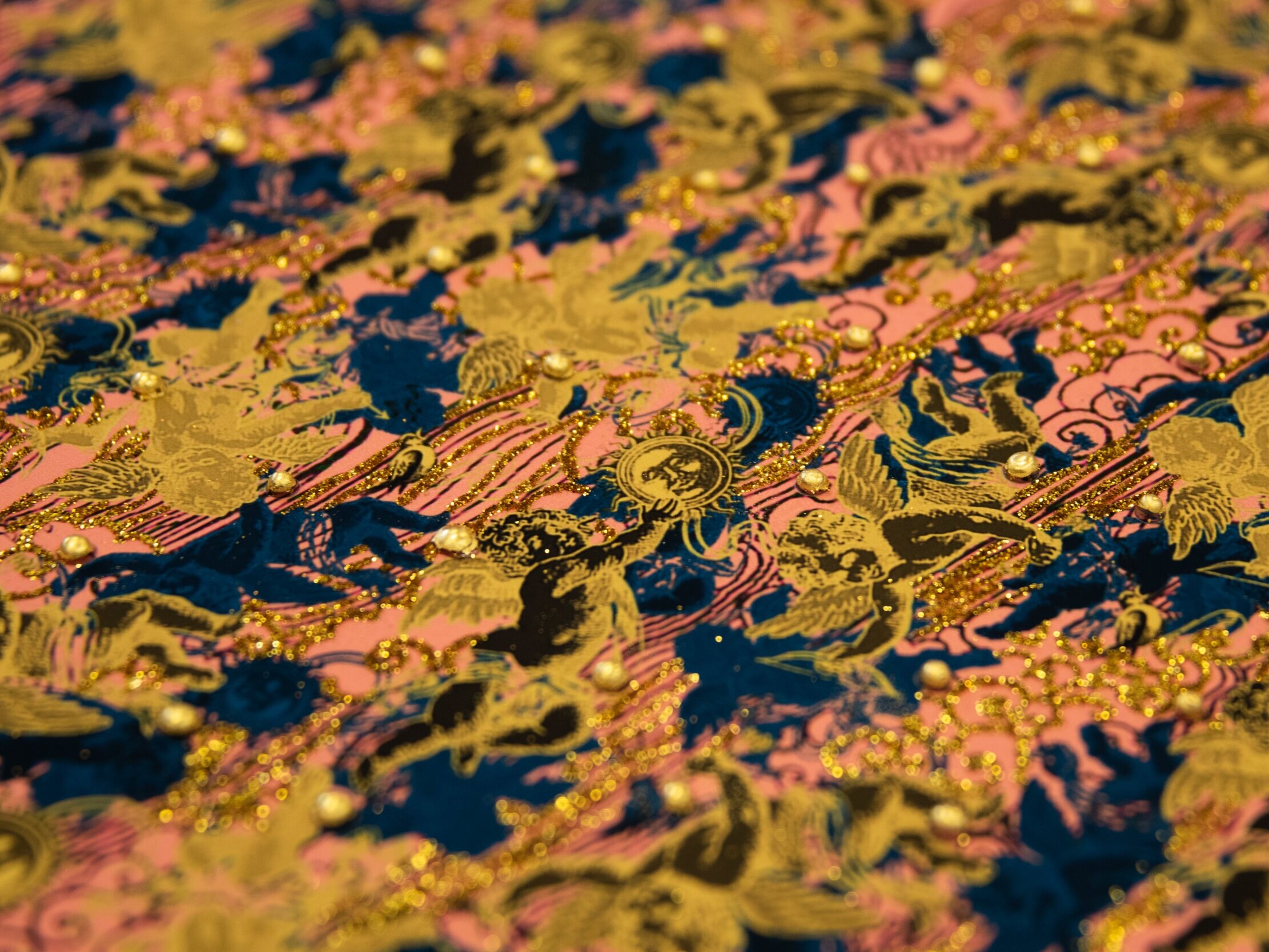

These complex works began as drawings, developed into hand-painted and silkscreen printed patterns. These have been digitised and retransformed into a repeat pattern in different bold vibrant colourways and embellished with diamond dust and gold, to create a sense of transcendent radiant light and add value. With these precious materials, I hope to reflect on the legacy of how value has been attributed to skin tone and to depict Heaven. The artwork is designed to be a sculptural object and has been painstakingly crafted by hand from painted metal and glass, embellished with 24ct gold leaf, referencing the iconic sunburst frame design.

The sunburst creates a burst of light and interest, but it is also designed as a metaphor for the world, it has spiritual energy and is never-ending, so it represents eternity. It also goes back to the Renaissance, at which time the circle was considered to be perfection, and perfection was equated with holiness and the magnificence of God’s creation.

The sunburst design itself dates back to King Louis XIV who used the head of Apollo surrounded by the sun’s rays as his personal emblem. Known as the sun king, Louis XIV famously transformed the Palace of Versailles, it was covered in gold to represent the divine right of the king to rule and to demonstrate his power. He used decadent imagery as a powerful tool of self-promotion and propaganda which was fundamental to the establishment of absolute power and authority of the monarchy. In my work, this symbol of Western glory has been re-imagined reflecting the glory of my little cherubs and a vision of the divine for us all.

Creating this work became an increasingly subversive act, both as an artist and in terms of the Western canon. As I made this work I became increasingly horrified on behalf of my children, and all BIPOC people around the world, at how subversive this was. This is reflected in the techniques and medium which also transcend the European tradition. I made this work in mixed media in order to confront the hierarchy of Western art, the distinction between “Major” and “Minor” Arts. Crafts and decorative arts have widely been seen as inferior in Western culture, largely due to the marginalisation of women’s work and non-Western artistic production. I wanted to reference textiles, embroidery, beading, wall-hangings, clothing, and jewellery, which are not only works of art, but can also be used as ritual items that play a spiritually significant role. I wanted to use the medium to challenge the idea that white men make art, and that women and non-western artists make “crafts”. I think in this way, it also challenges the idea of the solitary male artistic genius. I put in so much time, work, thinking, research, and experimentation to get to my final imagery - it’s not some flurry of what is often reported as a (usually) white masculine genius artistic expression.

The final artwork, therefore, plays with canonical modes of artistic production, but these are combined with non-Western techniques, imagery, and inspiration. This combination of the embellished cherub pattern rendered in modern and exciting colours and encased in the radiant frame creates a striking effect that can totally transform a space

To me, this work really came to be about divine inspiration and how this can help us to overcome challenges. As well as how this inspiration can give us the strength to challenge the dominant paradigms of artistic expression and representation, and the possibilities of art to construct alternative narratives. I hope this work shines a light on important questions about divinity, heritage, value, and norms.

I was really privileged to talk with Professor Martin Kemp from Oxford University about this new work. It was wonderful to hear from a world expert on how artists have captured the divine and get his take on this work!

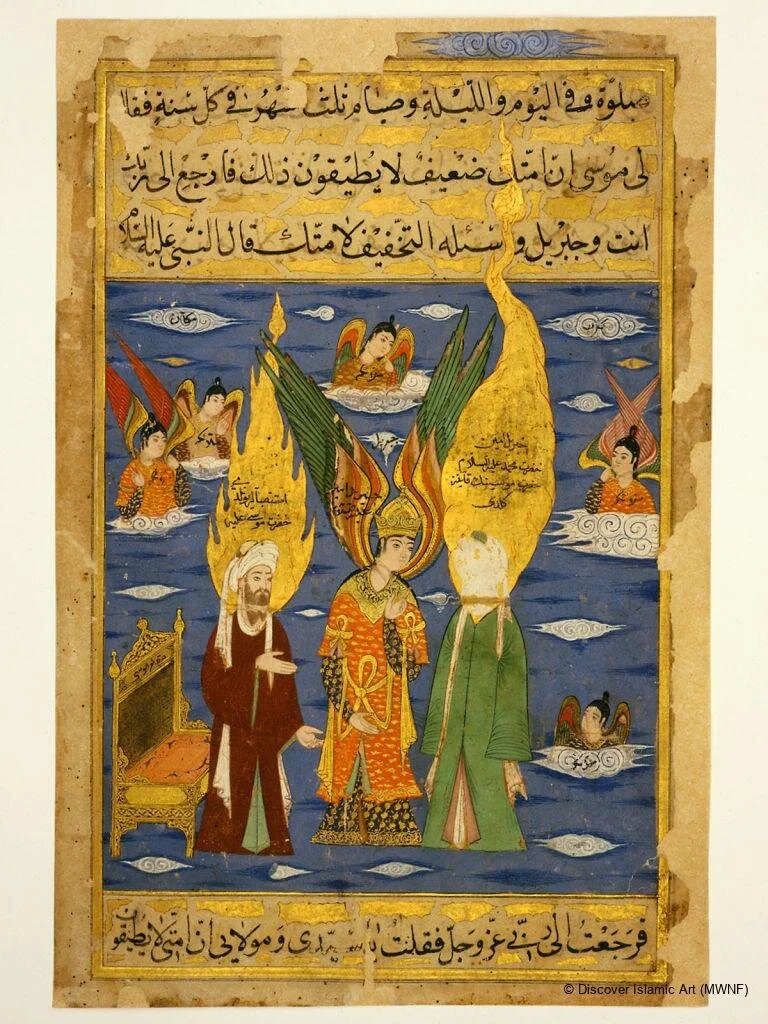

There are only a couple of notable exceptions to my observation that angels and cherubs are only ever depicted as white; Islamic illustrated manuscripts (below). Muslims believe that angels, or malaikah, were created by God and will exist until the end of time. Angelology in Islam is closely related to similar doctrines in Judaism and Christianity, for example, Jibrīl (Gabriel), the bringer of good news, is mentioned in both the Qur’an and the Hadith.

The other notable exception can be found in Ethiopian Christian art, notably the Debre Birhan Selassie Church in Gondar, Ethiopia. The ceiling of the church is completely covered by exquisite Christian Church art, including the faces of angels. The compound in Gondar city demonstrates a remarkable interface between internal and external cultures, with cultural elements related to Ethiopian Orthodox Church, Ethiopian Jews, and Muslims.

I came across this amazing image of a black angel thanks to the wonderful Instagram page @ablackhistoryofart . It’s a miniature painting from the Aurora Consurgens, an alchemical treatise, created in Germany in the 1420s.

If you are interested in any of the Sunburst artworks please visit my online viewing room here.